Ahmed Ibrahim Albooq

Prince Saud Al-Faisal Wildlife Center

Images by Olive Cope and Desica Cofly

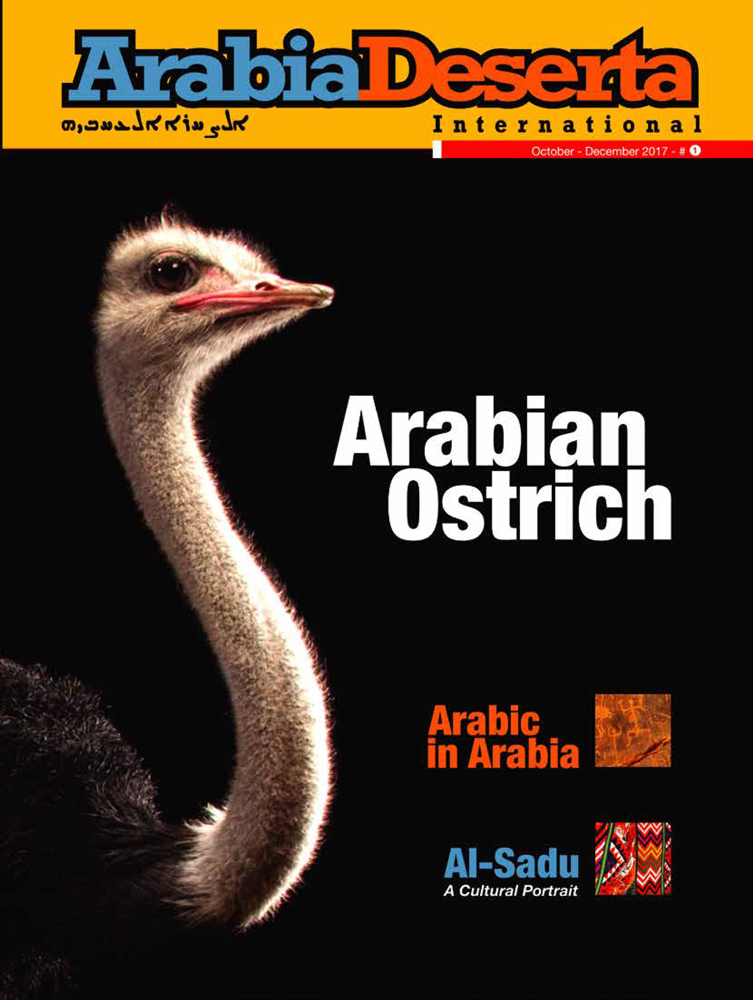

While flipping through an anthology of classical Arabic poems that depict Pre-Islamic natural and social conditions , art and life styles, I came across some new and fascinating facts about the famous Arabian ostrich whose last extant African-oriented cousins or subspecies are currently sheltered at Mahazat Assaid wild life reserve 150 miles East of Al-Taif. As a matter of fact, both the fauna and flora of Arabia are slipping away from our sight and memories and their inspirational power or what remained of it lies in the deep recesses of our poetic heritage.

Previously, ostriches lived all throughout the range of Africa and South of Sahara. These large birds are often found in open places such as savannas and grasslands. They also occupy forest zones in the Sahel of Africa. The ostriches are known to reside in the true deserts and semi-deserts. These flightless birds are never found at a height of 100 meters. By the middle of the 20th century, the ostriches were hunted to extinction in many parts of the world and especially in Arabia.

The common Arabic ostrich had a long and glorious history, which need to be re-written now, and everything has to insert in the first opening paragraphs as Marquez says of beginnings.

The common Arabian ostrich is particularly famous for its tantalizing feathers, colors, speed and semi-ritual mating dances. Through intensive investigations, I discovered that according to shape, color, sound or behavior the Arabian ostrich used to have 150 different names and has been glorified in 53 poetic vistas by 35 Islamic and pre- Islamic poets.

In 1877, a London publisher released a book titled “Ostrich Farming” by Julius Dumas and James Edmond. The book carried drawings showing the ways of hunting the animal-bird on horsebacks. The aim of Ostrich hunting in Arabia and elsewhere was to obtain three different types of feathers, the Hijazi, the Aleppian and the Yemeni to be used as decorative elements and as dusters. Its skin is good for leather products and its meat is marketed commercially, with its leanness a common marketing point. Arabian ostrich products used to be regularly sent to Europe and Egypt via Jeddah and Eden.

However, at the turn of the 20th century, the two ostrich sub –species’ locations in Arabia, one at the edge of Najd desert and the other on the North Western corner of the peninsula up to Aleppo were almost at the brink of extinction. In a research published in 1986, British ornithologist Michael Jennings maintains that the two ostrich species of Arabia were extinct by 1910 and 1939 respectively. There are some disparate but uncorroborated reports about ostriches in the sixties. It is also known that in1923 King Abdul Aziz made a gift of a couple of ostriches to the Queen of England. Eggs of the Arabian ostrich are still on display in the British museum.

A few years ago, with the assistance of some colleagues, I conducted a field survey of Orooq beni Memuaarid reserve and other sites in the Empty Quarter. In the course of this voluntary assignment, I collected 38 nests, an assortment of eggshells and 5 unscathed eggs. A university of Oxford’s carbon test of these eggs stated they had been left lying there some 50,000 to 1500 years ago. If the latter estimate is ever close to the point, it will mean that the poet Imru Al Quais was not just bragging when he wrote that he used to hunt ostriches at the edge of deserts to feed his lovers with their lean meat.

Previously, ostriches lived all throughout the range of Africa and South of Sahara. These large birds are often found in open places such as savannas and grasslands. They will also occupy forest zone in the Sahel of Africa. The ostriches are known to reside in the true deserts and semi-deserts. These flightless birds are not to be found at a height of a hundred meters. By the middle of the 20th century, the ostriches were hunted to extinction in the Middle East in general and Arabia desert in particular.

The ostrich or common ostrich (Struthio camelus) is either one or two species of large flightless birds native to Africa, the only living member(s) of the genus Struthio, which is in the ratite family. In 2014, the Somali ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes), the North African (S.C.Camelus), The S.C.Massaicus, the South African (S.C.Australis) and the Arabian S.C.Syriacus were recognized as distinct sub-species. Unfortunately, SC Syriacus or the Arabic form of the ostrich is irretrievably extinct and the order now is being desperately revived through its African-oriented cousins or subspecies nat Mahazat Assaid wild life reserve 150 miles East of Al-Taif.

Diet and Physical Features

The Arabian ostrich’s diet consists mainly of plant matter, though it also eats invertebrates. Like all other social animals, it lives in nomadic groups of 2 to 5 birds but the number might grow to a 100 after inclusion of the new burgeoning offspring and adults. The ostrich is distinctive in its appearance, with a long neck and legs, and can run at up to about 50 km/h the fastest land speed of any bird. The common ostrich is the largest living species of bird and lays the largest eggs of any living birds. The avearage weight of the male is 100-130 kg and that of the female is 90-110 kg. When threatened, the ostrich will either hide itself by lying flat against the ground, or run away. If cornered, it can attack with a kick of its powerful legs.

The long neck is an adaptation that appears to aid in running. The long neck and legs keep their head up above the ground, and their eyes are said to be the largest of any land vertebrate helping them to see predators at a great distance. The eyes are shaded from sunlight from above. However, the head and bill are relatively small for the birds’ huge size.

Their skin varies in color depending on the subspecies, with some having light or dark gray skin and others having pinkish or even reddish skin. The strong legs of the common ostrich are non-feathered and show bare skin: red in the male, black in the female. The tarsus of the common ostrich is the largest of any living bird.

The bird has just two toes on each foot, with the nail on the larger, inner toe resembling a hoof. The outer toe has no nail. The reduced number of toes is helpful for getting away from predators. Common ostriches can run at a speed over 50 km/h and can cover many miles in a single stride. The wings reach a wide span and the wing chord measurement is about the same size as for the largest flying birds. The feathers lack the tiny hooks that lock together the smooth external feathers of flying birds, and so are soft and fluffy and serve as insulation. Common ostriches can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. In much of their habitat, temperatures varies between night and day. Their temperature control relies in part on behavioral thermoregulation. For example, they use their wings to cover the naked skin of the upper legs and flanks to conserve heat, or leave these areas bare to release heat. The wings also function as stabilizers to give better maneuverability when running. Tests have shown that the wings are actively involved in rapid braking, turning and zigzag maneuvers.

The Mating Dance and Reproduction

Male ostriches in the wild, or in large domestic flocks, are often seen leading around a small group of females. Males usually fight for a harem of 2-5 and more. The males are slightly larger than the females and darker in color. The male performs elaborate dancing displays, during mating season, trying to attract the female birds to mate with him. Mating season for ostriches extends for six months, with the chicks hatching about six weeks after incubation.

Male ostriches undergo a color change at breeding season, when his skin turns bright red, which signals the hens that he is ready to mate. The male attracts as many hens as possible by dancing, fluffing his feathers, flapping his wings and swinging his head around while getting down on his knees. Often the females play hard to get and just walk away but the male does not give up and continues until the females succumb to him.

The male ostrich is normally a silent bird and it is almost the only bird equipped with a male organ. During the breeding season, he finds his voice and makes loud, hollow-sounding booms to attract hens. This vocalizing, along with his strutting and dancing, is what makes the hens become attracted to him rather than to the other males in the area. The loudest voice (booming) and the fanciest dancing technique is what makes him a successful breeder and attracts more females to his harem. The booming range corresponds to 2-15 sq. kilometers of land area over which the male ostrich has full sovereignty and does not tolerate any form of competitive male forays, incursions or trespassing.

The female ostrich holds her wings out from her sides, shaking the tips. She bobs her head, holding it low while opening and closing her beak. She crouches, telling the male she is ready. He approaches her with a rapid footwork dance and then mounts her while crouching with one foot on the ground and the other on her back.

Ostrich males are not monogamous during breeding, but do consider the dominant hen who also is called the major hen. This hen gets first choice of nesting grounds, lays her eggs first, and then allows the other females in the flock to lay their eggs. The major hen knows which eggs are hers and protects them by pushing away the eggs of other hens. Those eggs are more likely to be eaten by predators.

Ostriches attain the maturity age after 2 – 4 years, with females being mature six months earlier in comparison to the males. More than 90% of nests might end up in predation and only 10% survives in the end. The longest life expectancy range for an ostrich in the wild is 30-40 years and 50 years in captivity.

The North African ostrich is the closest relative to the Arabian ostrich from Western Asia. Following analyses of DNA that confirmed the close relationship of the Arabian and the North African subspecies, the latter was considered suitable for introduction into areas where the Arabian- Syrian subspecies used to live.

In 1988-89, the ostriches, originally taken from North Africa, were introduced to National Wildlife Research Center in Saudi Arabia. The reintroduction project using the North African ostriches was set up at Mahazat Assaid Protected Area in 1994. Currently, it is estimated that 90 to 100 individuals are living within the reserve.

As we said in the opening paragraphs, Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry is renowned for its vivid descriptions of the Jahili environment. Particular attention have to be paid to the ways in which poets depicted animals and other aspects of nature and often indulged in complex patterns of imagery that likened attributes of one animal to those of another. The images of camels and horses—the two mainstays of the tribe’s mobility—in pre-Islamic poetry are justifiably well known. Imruʾ al-Qays,“The Torchbearer of Arabic Poetry” describes his horse:

He has the loins of a gazelle, the thighs of an ostrich; he gallops like a wolf

and canters like a young fox.

By contrast, relatively little study has been devoted to treatment of animal images in the works of Antara ben Shad dad and Zohair Ibn Abi Salma. In fact, amongst the animal tableaus in their poems is a recurrent grouping of animals consisting of the Oryx, the Arabian onager, and the Arabian ostrich. The latter two species are now extinct and differ from the modern wild ass and African ostrich. Therefore, future research should focus on analyzing the Oryx, onager and ostrich tableaus and to establish that they are a coherent group that signal a particular social context.

The common Arabian ostrich is particularly famous for its tantalizing feathers, colours, speed and semi-ritual mating dances

Previously, ostriches lived all throughout the range of Africa and South of Sahara. These large birds are often found in open places such as savannas and grasslands

The long neck and legs keep their head up above the ground, and their eyes are said to be the largest of any land vertebrate helping them to see predators at a great distance.

Male ostriches in the wild, or in large domestic flocks, are often seen leading around a small group of females. Males usually fight for a harem of 2-5 and more.

In 1988-89, the ostriches, originally taken from North Africa, were introduced to National Wildlife Research Center in Saudi Arabia. The reintroduction project using the North African ostriches was set up at Mahazat Assaid Protected Area in 1994.